At the start of the 20th Century, an Italian physician named Dr. Maria Montessori founded a theory of education which she developed over many years of observational analysis of the use of various methods of educational activity and experience which made use of the five senses and of muscle memory, with children aged two to three and six to seven and with mentally disabled children.

The philosophy behind her theory was that there should be a focus on a child’s individual strengths rather than their weaknesses, and that each child should be provided with a supportive environment.

The Montessori method of education laid out some key principles such as:

- Freedom of movement and freedom of choice

- Structure and order in the arrangement and sequence of any materials – using materials that provide active learning experiences and reflect the reality of life, not fantasy

- And in an environment that is attractive, warm and inviting and also facilitates a closeness to nature and the natural world

With an emphasis on:

- Touch and the use of hands and the five senses to stimulate the mind, especially with natural materials

- Focusing on the task at hand

- Preparation of the environment to meet the needs of the individuals using it

- Guided repetition and the breakdown of tasks

Dr. Montessori’s first Casa, or Montessori School, was established in Italy in 1906 where 50-60 children took part in a broad range of activities which encouraged care of the environment and the self, such as flower arranging, gardening, hand-washing, gymnastics, care of pets and cooking. The Casa’s environment was also readjusted – heavy school furniture was replaced with child-sized tables and chairs that were light enough to be moved by the children and the child-sized Montessori materials were placed on low, accessible shelves.

Over one hundred years later, her theories are still in practise in pre-school Montessori nurseries around the world, and much more recently, her theories have been put into practise in dementia care settings.

During Dementia Awareness Week in May 2013, Judith Potts wrote an article in The Telegraph in which she expressed her own interest in the Montessori schooling method, and started to investigate its possible use in caring for those with dementia.

In the article she mentions Dr. Cameron Camp, who, since the early 1990s, has been working at the Myers Research Institute in Ohio, researching the use of the method in the institute’s dementia programme. Dr. Camp is also the creator of MBDP or Montessori-Based Dementia Programming, which takes the Montessori method and adapts it for people with dementia, forming the idea that by finding the person behind the dementia, caregivers can find clues about how to strengthen their brain function. Reports state that Dr. Camp has proven that by using MBDP there are increased levels of participation and engagement in those taking part.

Potts also mentions two other Americans using the Montessori method in their work with those with dementia: Tom and Karren Brenner train family, caregivers and medical staff in the Montessori method of dementia care and have written a book, ‘You Say Goodbye and We Say Hello: The Montessori Method for Positive Dementia Care’. One reader’s review on Amazon reads, “They really talk about how to find activities which are meaningful to the person. The same activity will not reach every person the same and sometimes an activity you assume someone will not enjoy, they absolutely love. It is all about getting to know the person as best you can and also trying new things with them to see what will reach them.”

The idea around the Montessori method for dementia is based around the five senses and muscle memory. As muscle memory still works for those with dementia, activities such as flower arranging and sorting objects can be enjoyable and, equally important, achievable processes that can help to reduce the fear and frustration often experienced.

L’Chaim retirement home in Toronto in Canada is an example of a home that is benefiting from introducing the Montessori method into its care practises. Tralee Pearce, in an article in the The Globe and Mail, describes a man, a retired cardiologist, sitting in his chair at the home sorting through cardiograms – an activity he’s been given to keep what memory he has left, active. And at their daycare centre in the Greater Toronto area, Pearce comes across two ladies rolling out cookie dough and sprinkling nuts over it, one who is known to have been a keen baker.

For the men and women who attend the day centre there is also a table set-up with activities including a basket of towels to fold and a bin of tubing and plumbing connects to put together and take apart, described in the article as ‘adult Lego’.

These activities invite some familiar and sometimes repetitive actions, accessing a stored muscle memory which then helps to give the person with dementia a sense of achievement, satisfaction and comfort, and also curb feelings of frustration and isolation.

The centre is also a Montessori example in its environment as well. Everything is labelled in large legible signage so that no one risks being scared by not knowing what is what. And the exit doors are camouflaged by tromp-l’oeil paintings of furniture to prevent anxious habits such as exit seeking.

Judy Cohen, the home’s manager, quoted in 2012 said this of the Montessori method,

“My entire outlook on dementia care changed. I began to see the “person” behind the dementia. Using the Montessori philosophy, we engaged each resident in meaningful activities, regardless of how advanced their dementia was. Before I knew it, I was running a full-day program for my residents from 9 a.m. – 4 p.m. They were engaged in life! I quickly noticed a reduction in depression, anxiety, repetitive questioning and other behaviors associated with dementia. More importantly, I saw an increase in self-esteem. The residents felt like they were needed and were contributing to their community.”

In the UK, Fiona Fowler and Alistair Richardson of Dementia Works provide training and consultancy in many areas of dementia care, including the Montessori method.

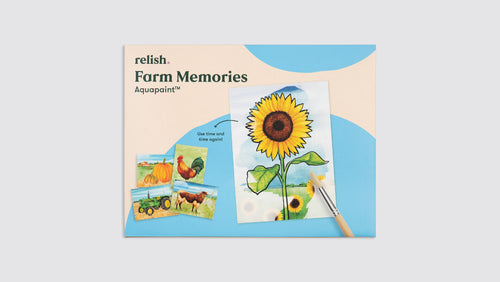

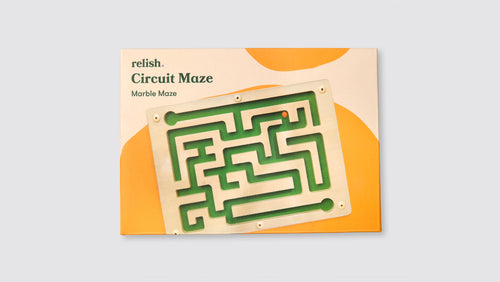

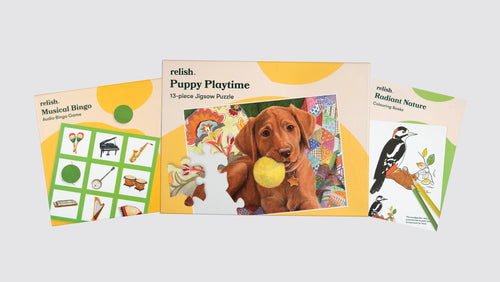

Following Montessori principles, stage-appropriate dementia gifts that match the person’s abilities can promote independence and a sense of accomplishment.